Storm Chaser Down Under

Storm chaser down under

A British photographer made the lightning decision to quit the UK to chase storms Down Under and was rewarded with these striking shots. Oliver Kay, 40, left his dead-end IT job in Manchester almost a decade ago with wife Helen in search of a new life in Perth, Western Australia. He mixes a job with one of Perth’s biggest mining companies with his weekend passion of photography. And Oliver struck gold after being woken up by thunder at 3.30 in the morning and taking amazing pictures of lightning filling the sky above Hillary’s Marina in his adopted home city. (Caters News) Photography by Oliver Kay

See more storm photos and our other slideshows on Yahoo News.

More Posts from Thekrishankumar and Others

Between 470 million to 760 million people worldwide could lose their land to rising seas if global warming is allowed to continue unbridled, says a study conducted by scientists at Climate Central, a nonprofit research and news organization. In this photograph by Shahria Sharmin of @ap.images, Saleha, 38, who lost her land to river erosion, stands in a field that she farms with her husband in exchange for a place to stay in the island district of Bhola, where the Meghna River spills into the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh. For more on the UNited Nations Climate Change summit in Paris, France, visit TIME.com. http://ift.tt/1RnIReR

The real importance is not just the people who want to go into tech jobs, we believe that a basic understanding of how technology works is important to all jobs.

Hadi Partovi, our co-founder and CEO, on why we need more diversity in computer science. (via codeorg)

Beautiful.

Photos of the day - October 12, 2014

Runners participate in the Chicago Marathon, Ultra-right wing anti-separatists burn flares during a demonstration for the unity of Spain as they celebrate Spain’s National Day in Barcelona and a folk artist wearing a traditional headdress to mark the third anniversary of Yakshagana Kala Sangha in Bangalore are some of the photos of the day. (AP/Reuters)

Find more news related pictures on our photo galleries page and follow us on Tumblr.

AM & FM: How Radio Works

Lately I’ve been thinking about how the things I use every day actually work, and since I listen to a lot of podcasts, you can guess where this post is going: radio.

In a studio, a microphone converts sound waves from a person’s voice into an electronic audio signal. If this was sent out by itself, it would only travel a few metres in air before it faded out. To get radio waves to travel long kilometres to a receiver, we have to combine it with a “carrier wave”—an electromagnetic wave.

Electromagnetic waves are made up of oscillating electric and magnetic fields, just like visible light, but radio waves are right down on the lower end of the spectrum, so their wavelengths are very long—around 300 metres.

(Image Credit: NASA)

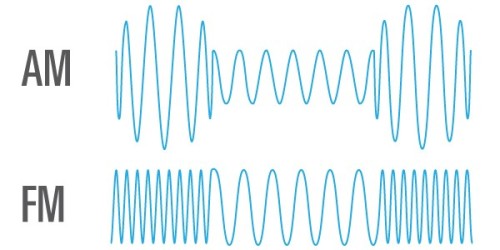

Sound information is combined with the wave by altering or modulating the wave’s properties, like changing its amplitude, frequency, or phase. There are two ways to combine the audio signal with the carrier wave: amplitude modulation (AM) or frequency modulation (FM).

AM radio changes the overall amplitude or strength of the wave, varying its height in order to incorporate the sound information. FM radio works a little differently, because it changes the frequency of the wave rather than the amplitude. The frequency is the number of wavelengths that pass by a given point per second—physically, a high frequency wave would look squashed up, and a low frequency wave would look stretched out.

(Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Both kinds of waves are susceptible to variations in amplitude as they zoom off through the air, but since FM radio relies on changes in frequency rather than amplitude, these variations don’t matter—they can just be ignored, and so the sound quality is usually super clear. But AM radio relies on the amplitude to convey information, so when the amplitude is varied a bit, this results in interference or static, which will be a familiar idea if you’ve ever listened to AM radio on a rural country road. The upside of AM radio is that it travels much further than FM radio, which is probably why you’re listening to it on that rural country road in the first place.

So once these radio waves—whether AM or FM—hit a radio receiver, their oscillating fields induce a current in the conductor. The sound information encoded into the waves can be extracted, and converted back to sound waves to grace your ears with your favourite music or talk show.

(Bonus: if you want to use science to learn more cool science, my fave podcasts are Radiolab, the Infinite Monkey Cage, and Big Picture Science.)

'A Conspicuous Fishing Village' Dubai, UAE

By Freddie Ardley Photography

Website | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter

-

nakedgirldd liked this · 10 years ago

nakedgirldd liked this · 10 years ago -

mostlonely reblogged this · 10 years ago

mostlonely reblogged this · 10 years ago -

shutthefuckuphannah reblogged this · 10 years ago

shutthefuckuphannah reblogged this · 10 years ago -

pomegranates33d liked this · 10 years ago

pomegranates33d liked this · 10 years ago -

blondie-chan reblogged this · 10 years ago

blondie-chan reblogged this · 10 years ago -

icefang111 liked this · 10 years ago

icefang111 liked this · 10 years ago -

r0se-j reblogged this · 10 years ago

r0se-j reblogged this · 10 years ago -

luper-ca1ia reblogged this · 10 years ago

luper-ca1ia reblogged this · 10 years ago -

lvthxr reblogged this · 10 years ago

lvthxr reblogged this · 10 years ago -

whateverpeoplethink reblogged this · 10 years ago

whateverpeoplethink reblogged this · 10 years ago -

screwyouiamtheavatar reblogged this · 10 years ago

screwyouiamtheavatar reblogged this · 10 years ago -

screwyouiamtheavatar liked this · 10 years ago

screwyouiamtheavatar liked this · 10 years ago -

cru-dem reblogged this · 10 years ago

cru-dem reblogged this · 10 years ago -

young-and-lonley-blog reblogged this · 10 years ago

young-and-lonley-blog reblogged this · 10 years ago -

just-daddy-and-princess reblogged this · 10 years ago

just-daddy-and-princess reblogged this · 10 years ago -

traumafood reblogged this · 10 years ago

traumafood reblogged this · 10 years ago -

traumafood liked this · 10 years ago

traumafood liked this · 10 years ago -

hackergurl liked this · 10 years ago

hackergurl liked this · 10 years ago -

the-music-attracts-me reblogged this · 10 years ago

the-music-attracts-me reblogged this · 10 years ago -

the-music-attracts-me liked this · 10 years ago

the-music-attracts-me liked this · 10 years ago -

mode-maude-maudie reblogged this · 10 years ago

mode-maude-maudie reblogged this · 10 years ago -

becausewhyn0t reblogged this · 10 years ago

becausewhyn0t reblogged this · 10 years ago -

newyorkmess reblogged this · 10 years ago

newyorkmess reblogged this · 10 years ago -

huntergyoumans liked this · 10 years ago

huntergyoumans liked this · 10 years ago -

lionelfaucher reblogged this · 10 years ago

lionelfaucher reblogged this · 10 years ago -

bigtexx reblogged this · 10 years ago

bigtexx reblogged this · 10 years ago -

opieparadisia reblogged this · 10 years ago

opieparadisia reblogged this · 10 years ago -

opieparadisia liked this · 10 years ago

opieparadisia liked this · 10 years ago -

gordonovan liked this · 10 years ago

gordonovan liked this · 10 years ago -

peekay2601 liked this · 10 years ago

peekay2601 liked this · 10 years ago -

itsyounggg reblogged this · 10 years ago

itsyounggg reblogged this · 10 years ago -

sharvanaa liked this · 10 years ago

sharvanaa liked this · 10 years ago -

everyhthing-happens-for-a-reason liked this · 10 years ago

everyhthing-happens-for-a-reason liked this · 10 years ago -

martyarcher liked this · 10 years ago

martyarcher liked this · 10 years ago

16, I love Technology & Science Stuff . krishan@krishankumar.me

82 posts